Killing of top Nazi ‘butcher’ – soon to be subject of Jamie Dornan movie – led to 10,000 deaths after Hitler unleashed merciless vengeance

New film Anthropoid, starring Cillian Murphy and Jamie Dornan, looks at Reinhard Heydrich assassination and the thousands of innocent civilians that were slaughtered as a result

IT was an audacious, stunning blow to Nazi Germany – yet it came with a terrible price.

The assassination at the height of World War Two of top SS officer Reinhard Heydrich — the “Butcher of Prague” — unleashed a merciless vengeance from Hitler, with thousands of innocent civilians slaughtered.

Now a new movie starring Cillian Murphy and Fifty Shades of Grey star Jamie Dornan highlights the heroism of Operation Anthropoid.

Anthropoid hits cinemas on Friday and also tells of the Nazis’ barbaric reprisals — which were so harsh that some wonder if the assassination was truly worthwhile.

Marie Supikova was ten when her entire village was wiped out in revenge for the assassination — she can’t bring herself to watch the film.

In 1942 the Germans had overrun her Czechoslovakian homeland and Russia seemed set to fall next.

Winston Churchill’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Czech government-in-exile were desperate for any kind of victory to boost morale.

Heydrich was head of Nazi security and the man Hitler put in charge of exterminating Europe’s Jews.

He was also temporary dictator of the Czech provinces, ruling with an iron fist to ensure the factories kept churning out war machinery. He was an obvious target for assassination.

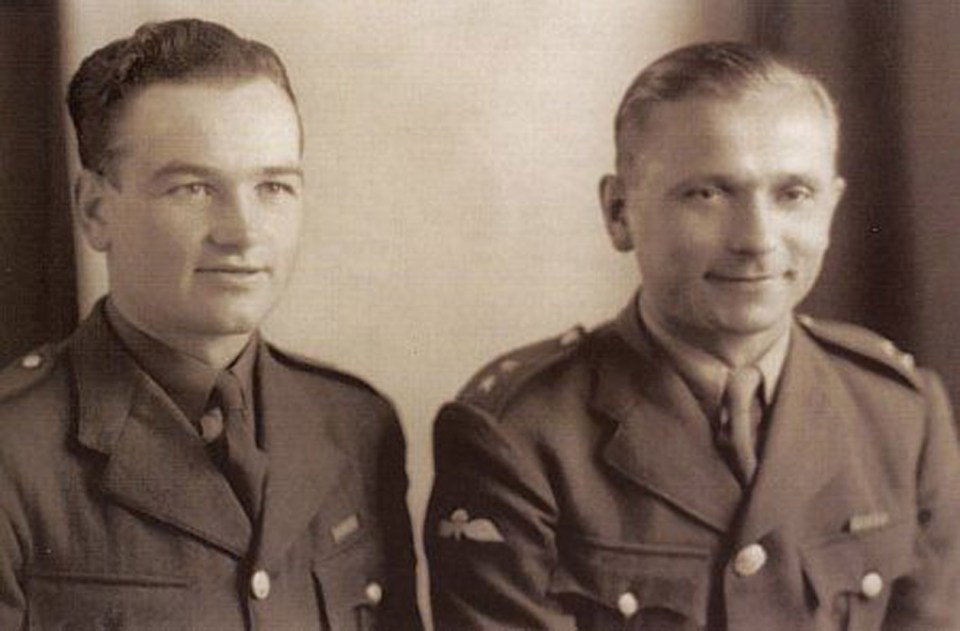

Slovak Jozef Gabcik and Czech Jan Kubis — played by Murphy and Dornan — were parachuted close to Prague to carry out the high-risk mission.

On May 27, 1942, they waited at a sharp turn in a Prague road where they knew Heydrich’s open-top Mercedes would be forced to slow down.

As it did so, Gabcik leapt into its path — but his sub-machine gun jammed.

When Heydrich stood to shoot him, Kubis threw an anti-tank grenade in a briefcase at the car. Shrapnel peppered the SS man.

Heydrich tried to give chase but collapsed. His driver was also injured but the assassins escaped thinking they had failed.

Heydrich would die of blood poisoning a week later. But by then Hitler had already ordered brutal reprisals.

As Gabcik and Kubis went to ground, 13,000 civilians were arrested — including Kubis’s girlfriend, who would later die in a concentration camp along with countless others. False reports linked the agents to the village of Lidice, close to Prague.

Near midnight on June 9, German troops stormed the village. They set up their HQ in the first house they came to — that of Marie’s Supikova’s family.

All 173 male villagers over 16, including Marie’s father Josef Dolezal, were rounded up and executed in cold blood.

Nearly 300 women and children were taken to a school gym in nearby Kladno, while every building in Lidice was burned then bulldozed.

Marie now 94, says: “We did not get to say goodbye to my father. A soldier came and separated my father from my mother, my brother Josef and I.

“That was the last I remember of him. In the gym we waited on floors covered with straw for three nights. We had no personal belongings, just the clothes we wore when we were driven from our homes. When they separated us, there were terrible scenes.

“Mothers did not want to give up their kids and the kids did not want to break away from their mothers. It is impossible to forget those scenes. The air was filled with cries until one of the Gestapo fired a warning shot.

“In the confusion that followed, the soldiers took us children away and began to classify us by the colour of our eyes, our hair, our height and age.”

Her brother and other boys and girls over 14 were taken to Prague to be executed as adults. While the women were transported to concentration camps, 89 other children were taken to an orphanage at Lodz.

Marie said: “I don’t know how long we were there. Ten days? Fourteen? I recall only that we slept on the ground. It was cold and we were hungry. Our clothes were torn and dirty and we could not wash. We all had lice.

“Then there began another selection. An SS man walked among us in his high leather boots, carrying a pointer with which he occasionally tapped someone on the shoulder. Why he tapped me I had no idea.

“I didn’t have really blonde hair but I am very lucky I was chosen. They chose six girls from Lidice and among us were two sisters who began to scream that they must take care of their little brother because they had promised their parents they would. The SS men allowed them to take their brother with them, so there were seven of us.”

The other 82 children were gassed at Chelmno extermination camp in Poland.

With the SOE agents still at large, the Nazis gave the Czech people an ultimatum: Give up the assassins or face yet more bloodshed. It proved unnecessary.

The Gestapo questioned resistance suspect Karel Curda and he betrayed the saboteurs’ safehouses for one million Reichsmarks. At dawn on June 17, the home of the Moravec family was raided. Marie Moravec bit into a cyanide capsule and killed herself.

Her husband Alois and son Ata, 17, were taken away for torture. The Gestapo showed Ata the severed head of his mother and said his father would be next unless he talked. He named the Prague church where Gabcik, Kubis and others were holed up.

Related stories

The movie recreates the extraordinary scenes as 750 German troopers laid siege to the church. The drama lasted for four hours until Kubis died from his injuries, while Gabcik and others killed themselves in the church’s crypt rather than be taken alive.

To prevent further persecution of his people, Bishop Gorazd of Prague claimed responsibility for hiding the assassins.

He was tortured and shot — but the Nazi atrocities went on.

A resistance radio found in the village of Lezaky in September 1942 doomed it to the same fate as Lidice. All 33 adults were executed, with two children sent for “Germanisation”, like Marie Supikova, and 11 others gassed at Chelmno.

A month later, Ata Moravec was executed at Mauthausen, in Austria, along with his father, his fiancée, her mother and her brother. After being picked out by the Nazi officer, Marie was adopted by a German couple, Ilse and Alfred Schiller, in occupied Poland.

She says: “They were an older couple and didn’t want to be alone. They were good people, I liked them. It was the only way to survive in even slightly normal conditions.

“I called them Mum and Dad. They had two dresses waiting for me. One was blue and white plaid and the second was dark blue with red dots.

“I was lucky. Those of us who were adopted were sent to selected families who guaranteed a German education and loyalty to the Reich. But for the Schillers it was more a question of humanity.”

After the war, Mr Schiller learned of efforts to trace the missing children of Lidice and took Marie to Berlin.

She says: “I had no chance to say goodbye. Mr Schiller took me to a place where I was handed over to officials. The door opened, I went through it and the door closed.

“I never saw the Schillers again. It was the second time as a child I had been taken from my family.”

Marie, by then 14, learned for the first time the full horror of what happened in Lidice and that only her mother had survived from her family.

They were reunited but her mother had advanced tuberculosis and Marie then spoke only German. They had just four months together, communicating via an interpreter, before her mother died.

After Lidice was rebuilt, Marie, now married with children, was given a house in the new village. To this day she helps out in the museum, telling of the heroism and horror of Operation Anthropoid.

She won’t talk about Gabcik and Kubis, however, saying only of the mission: “Every person has a different perspective.”