Bristol University in the dock after 10 suicides and sudden deaths in 18 months

Bristol University stands accused of overselling student glamour with immature teens unable to cope with the reality of life away from home

WITH its glittering academic record and nightlife, Bristol University has a well-deserved reputation for being one of Britain’s top places to study.

But a long shadow now lies over the city after ten suicides and sudden deaths among its 23,500 students in just 18 months — including three in three weeks this term alone.

There are many competing theories about the spate of deaths, including inadequate pastoral care, low-grade university accommodation and a student body increasingly remote from older, wiser academic staff.

Social media has also been blamed for pressuring youngsters to present a perfect image of their lives so friends fail to notice sadness creeping in.

And there is also concern that the university is overselling a gilded version of student life to woo teenagers — some of whom are not mature enough to cope — in order to land annual tuition fees of £9,250.

The mother of one victim complained academia is now merely a business whose main aim is to get “bums on seats”, and even that Bristol is trying to “cover up” the deaths.

Certainly feelings are running high on campus, and an undergraduate march is planned for next Friday.

March organiser Robin Boardman said this week: “The recent student deaths are a tragedy and the university’s response has been appalling.”

Yet behind every theory is the heartbreaking story of another young life cut short.

Ben Murray, a first-year English literature student, was the latest to die, on May 5.

The university said his death was “not suspicious” and a coroner’s inquest will open shortly.

Last month Alex Elsmore and Natasha Abrahart also died in distressing circumstances.

Alex, 23, was the son of Guy Elsmore, the Archdeacon of Buckingham, and in the fourth year of an electrical and engineering degree.

He lived in Manor Hall, one of Bristol’s smartest halls of residence that costs about £5,500 a year.

It lies in the upmarket suburb of Clifton, less than a mile from the main campus, and is surrounded by green spaces and trendy bars.

Alex is thought to have fallen from the nearby Clifton Suspension Bridge on April 21.

Nine days later it was reported that Natasha, 20 — in her second year studying physics — had also died unexpectedly.

She also lived within a mile of the main campus but her privately rented accommodation — a first-floor flat above a restaurant — was rougher around the edges.

This week one of the restaurant staff confirmed a young woman was taken away by ambulance after firemen broke down her bedroom door.

She said: “It all happened so fast.”

Just as in the case of Ben, no inquest has yet been heard into either death.

There is no clear link between them and the three are not thought to have been friends.

Neither is there any known connection between the six students who died between October 2016 and October 2017, or the seventh who died in January this year.

So what is causing these tragedies?

A Bristol University spokesman said it had pledged last September to spend £1million on “wellbeing advisers” and has committed to hiring a team of full-time mental health advisers and managers.

Fifteen have now been appointed and the university says 18 more places will be filled next month.

Now, as A-level students around Britain prepare to sit their final exams over the coming weeks, one grieving mother told The Sun parents must weigh up if university is the right choice for their child.

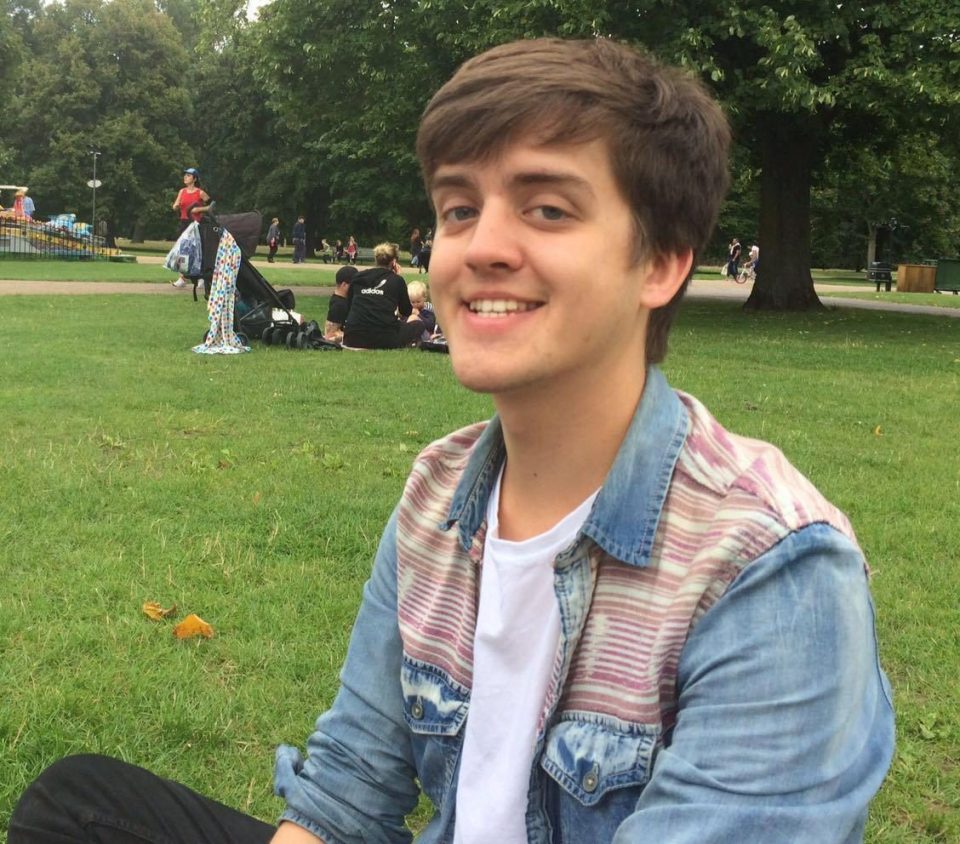

Diana Thomson’s son James, 20, took his own life last October while reading maths at Bristol.

Pilates teacher Diana, 63, from Northampton, said: “The coroner said there was no link between any of these deaths but there is one — Bristol University.

“Universities generate millions of pounds in income through fees.

"But what are you paying £9,250 a year for? When we first looked around we were shown good accommodation and facilities.

“But this was not the reality. James lived in a tower block overlooking a multi-storey car park. I realise now it must have been very isolating.

“The heating didn’t work. There was one shower shared by five people. And in his lecture theatre there wasn’t even room for everyone to sit. People would sit on the floor.

“There was minimal pastoral care and no real contact with tutors.

"Something needs to be done to stop this myth being peddled that everyone should go to university.

"It’s all about money and getting bums on seats.”

Diana said James, who achieved a grade A* in maths and A grades in further maths and physics at A level, had no history of depression as a child.

She was surprised to discover after his death that he was prescribed anti-depressants by a GP while at Bristol.

Scores of other parents will have no idea their child has been prescribed pills while far away from home.

Diana added: “I don’t think parents know how universities have changed in the past ten or 15 years.

“It seems now everyone is pushed into university whether they want to go or not.

"They have no proper contact with adults. All James had to do was email his tutor three times a year.

“Nobody would know if a child was not coping.”

One thing that everyone agrees on is that Britain’s student population has expanded — and changed — dramatically in the last 20 years.

With half of all school leavers entering higher education before they turn 30, and with 2.3million students in the UK, universities now resemble the wider population far more closely than before.

This means the number of students with mental health issues is likely to be higher.

This month, new report Minding Our Futures — published by Universities UK, which represents 136 of Britain’s higher education institutions — issued a warning.

It called for better co-ordination between the NHS and universities after finding the number of students disclosing a mental health condition has rocketed from 9,675 a decade ago to 57,305 in 2017.

It also confirmed an increase in student suicides. In 2001, 108 were recorded.

In 2015 — the latest year for which figures are available — that number had risen to 134, the highest this century.

John de Pury, of Universities UK, said: “We’ve got a generation of young people who are slipping into real difficulties.

"This is the only age group where diagnosed mental health problems are on the rise and that’s principally among young women.

"We have some sense it’s to do with pressures and perfectionism and the new worlds of tech and 24-hour online connectedness. But we don’t know for sure.”

Diana Thomson is adamant that at Bristol there is a deeper problem that has not been addressed.

She said: “Children are applying to universities at the moment, so none of them are going to want headlines saying someone has died again, are they?

“They’re going to want to try to cover it up because they’re going to want to get their next cohort of students in.

"It’s a business involving millions of pounds and they have got to fill those places.”

More deaths

Daniel Green, 18. The fresher, studying history, was found dead in his room in university halls of residence on October 21, 2016.

Justin Cheng. The Canadian was in third year of a law degree when he was found dead, away from Bristol, on January 12.

Ben Murray. Was in the first year of an English degree when he died “suddenly and unexpectedly” on May 5.

And Sir Anthony Seldon, vice-chancellor of Buckingham University, agreed the pressures of student life may simply be too much for some 18-year-olds.

He said: “To move from living at home where their lives are organised is an almighty leap to moving away to university.

“There’s nothing in life like this jump. Schools need to do a lot more, and more needs to happen in year one at university.”

Meanwhile Professor Hugh Brady, Bristol’s vice-chancellor, yesterday apologised for the tragedies in Epigram, the student newspaper.

Asked about what he would say to students who feel they have been left down by the support services, he said: “I’m sorry.”

And he added: “We are only going to solve this together.”

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this article, please call the Samaritans on (free) 116123 or 020 7734 2800.

GOT a story? RING The Sun on 0207 782 4104 or WHATSAPP on 07423720250 or EMAIL exclusive@the-sun.co.uk