England star Jamie Vardy downed skittle vodka and tried to become a soldier after early struggles in his career

Star considered quitting the sport several times

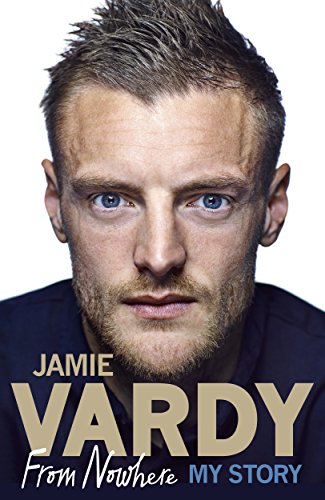

WHEN Leicester and England football star JAMIE VARDY was released by Sheffield Wednesday at the age of 16, it was just one in a series of knocks on his path to superstardom.

A decade later, in 2012, he signed for Leicester City for a non-League record £1million.

But there were times when he nearly quit football altogether.

Here, in our latest exclusive extract from his autobiography, Jamie recalls his lowest moments.

I CAN’T tell you who broke it to me that I “wasn’t big enough” to make it as a footballer. All I know is I walked out of Wednesday absolutely devastated.

I’d supported the club all my life and now they were telling me they didn’t think I had what it took to wear that shirt.

Anger and confusion were bubbling up inside. Everything I’d ever wanted had just been snatched away. Nothing made sense as I turned things over in my mind, wondering why they couldn’t give me more time to develop physically.

I sat my exams that summer and ended up with one GCSE at grade C and above. Everything else had passed me by.

Disillusioned and dejected, I went back to where it all started and played a few games for York County, not far from where I lived — but a million miles away from where I wanted to be.

I hadn’t prepared for failure. So there was nothing to fill that huge void. I was lost.

At one stage I even tried to sign up for the Army. I went to the recruitment office in Sheffield, started filling out the form and saw the section asking about criminal records.

I had to tell the truth — it would come up in a background check — so I circled “Yes” (from an assault charge for a fight outside a nightclub in 2007). I told them what had happened and they said there and then that I couldn’t apply.

It seems strange now to think I could have ended up on the front line. Maybe the discipline of the Army would have been good for me.

I took a job as a trainee joiner. As long as I had a few quid to go out for a couple of drinks, I was happy.

It didn’t take long to realise that being a joiner wasn’t what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. By the time I got home I was so knackered I’d go straight to sleep.

It wasn’t much of a life and within four or five months I packed it in.

I started working at the Trulife factory (making medical products) on February 1, 2007, three weeks after my 20th birthday, and spent more than four and a half years there. We had to clock in at 7.30am every day, Monday to Friday, which meant setting off at 7am. We’d clock out at 4.15pm, with a midday finish on Friday.

It was rewarding work but hard graft. I ended up with a lot of problems with my back. The fact I could stand in for my line manager was the only reason I didn’t get the sack for failing to turn up on so many Mondays. I took 36 off in one year alone and was nicknamed “Sicknote”. Generally, though, I was happy working there.

I was getting a full-time wage, a bit more than £1,000 a month after tax — more than enough to run a car and go out on a few evenings — and the job didn’t conflict with my football (with minor clubs), which was the most important thing.

We had a lot of laughs in the factory. Occasionally there was a chance to play a bit of football. We’d have a kickabout in the car park during break-time, especially in summer.

In those first couple of months at Leicester City I wasn’t exactly setting it alight on the pitch but things were going along OK.

We beat Burnley 2–1 at home (on September 19, 2012) and I got the winner, my first goal at the King Power Stadium, and at the end of September I scored again, the equaliser in a 2–1 victory at Middlesbrough, to make it four in nine appearances. But then the wheels came off.

I went nine games without scoring and one of the staff got an insight into the way I was living away from football.

Perhaps they’d already guessed but the proof was in the pudding — well, actually in my bloodstream — after I was kicked on my calf in a home defeat on October 27.

I had a dead leg — a fairly routine injury, but it was taking an age to get better.

I had a three-litre vodka bottle at home I would put loads of Skittles sweets in.

Once one batch had fully dissolved, I’d top it up with more — only the red or purple sweets because I don’t fancy the orange, green and yellow ones. I must have put a different batch in at least 20 times.

After that, you can drink the vodka neat and it tastes just like Skittles. When I was bored at home in the evening I’d pour myself a glass, sit back and enjoy. The vodka was decent but it wasn’t doing much for my dead leg, which didn’t stop bleeding for ages.

Dave Rennie, the physio, said he couldn’t believe it wasn’t improving. He’d seen a torn calf muscle heal quicker.

He pulled me aside one day when nobody else was about. “What are you doing?” Dave asked. “Nothing I wouldn’t normally do,” I replied.

Then I explained that what I’d normally do was drink Skittle vodka.

“Well, that will be why, then,” Dave said, looking a little shocked, before going on to explain the science behind it and how the alcohol was damaging the healing process. I got on a downer because the season wasn’t following the pattern of previous years, when I was used to scoring loads and being the main man. My way of dealing with that was to go and get p***ed with my mates in Sheffield.

related stories

My sleep pattern was screwed up. I’d invite friends to the apartment and sometimes we wouldn’t go to bed until 4am.

When I got home from training, I was knackered. If I put a film on I’d be asleep before the opening scene ended. Other days, I’d climb straight into bed in the afternoon.

Maybe my body wasn’t used to the intensity. Leicester was a massive gear change from what I was used to at my old club Fleetwood.

That siesta would turn into a full-on kip and there were times I wouldn’t wake up until 6 or 7pm. The knock-on effect was that I’d be wired at 3am.

A lot of the time I was on my own and that led to boredom. Sometimes I’d head to the Soar Point, a student pub in the university campus a couple of minutes from my place in Leicester. I had some proper sessions in there.

I wasn’t used to setbacks on the pitch and I’d never had so much money before, which allowed me to escape from things without any financial consequences. I’d scored 20-plus goals year on year, pretty much ever since I joined Stocksbridge and all of a sudden I was stuck on five.

I came to what I saw as the logical conclusion: This level is not for me. It wasn’t like me to doubt myself but for a while I was convinced I wasn’t good enough to play in the Championship. I found adapting to the standard really hard, especially in such a short space of time. I couldn’t give defenders a ten-yard headstart and outpace them any more. My runs had to be more intelligent.

I’m sure my teammates knew I was p***ing it up. Some were probably doing it as well, but they knew when and how often to do it.

I was confused and capable of coming out with anything, including a remark to a few teammates that I was thinking about becoming a rep in Ibiza. I seemed to have a habit of throwing Ibiza into conversations. It represented non-stop partying in my eyes.

I’d been happy there — and I wanted to feel happy again.

- Adapted by SEAN HAMILTON. Jamie Vardy: From Nowhere, My Story, Ebury Press, is out on Oct 6, £20.